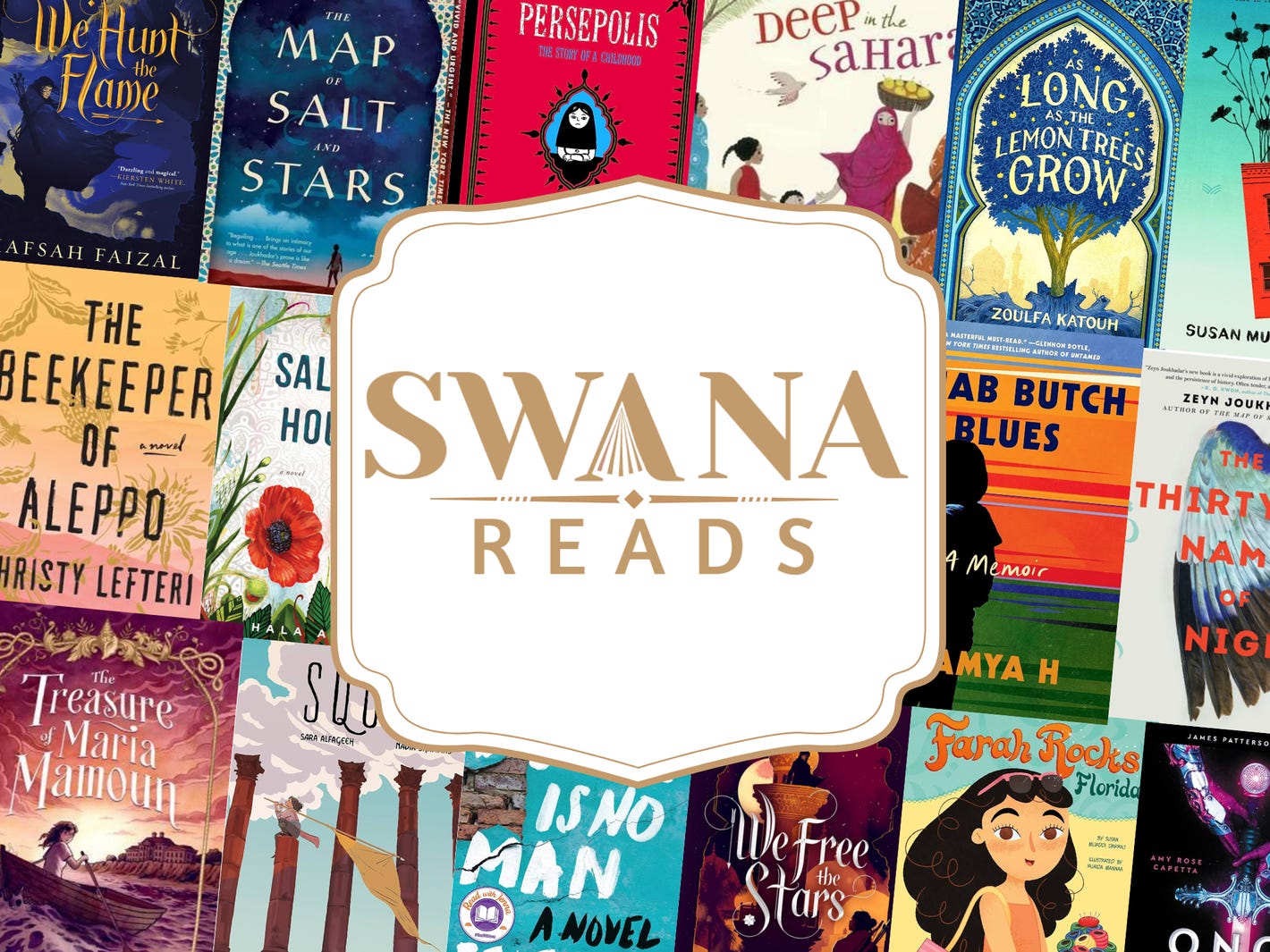

introducing SWANA Reads

aka my unemployment project

For Southwest Asian North African Heritage Month, a friend of mine and I collaborated on a database of book titles by and about SWANA people. You can find it here. For the last month or so, we have been compiling titles and authors in a gigantic spreadsheet and tagging them with all the demographic information your nerdy heart could dream of. You want to search by age category? Genre? Author’s background? We’ve got a filter for that.

The main reason I wanted to do this was because I noticed a severe lack of publishing industry support for SWANA authors and their books. SWANA is a relatively new term, one I have never actually seen in a published book. Sometimes, SWANA authors get included in the conversation around AAPI books, but this excludes the North Africans. Sometimes, well-meaning people try to produce reading lists for “Arab” authors, and end up including a bunch of non-Arab Muslims or even—non-Arab, non-Muslim, Persians.

This all links back to Orientalism. We are conditioned to think about “those people over there” and their cultural customs as indistinguishable. “Middle Eastern,” is a great categorization until you really think about what the “middle” of the East even means. Yeah, that’s the middle of the East if you’re standing smack dab at the center of London—the center of the universe, of course!

That’s why I like the term “SWANA” so much. It’s geographically accurate and it doesn’t mislabel anyone.

I love reading books about other SWANA cultures. I see the ways we are similar, and it makes me feel seen, but I also appreciate the ways that we are different and unique. I wanted to create a community for other SWANA writers where we could uplift one another without sacrificing our identities to some imaginary cultural monolith. I figured a database of books was a good place to start—and hopefully, teach readers a few things along the way.

Often times, when you ask a marginalized writer why they write, you’ll hear an answer along the lines of, “I want to write the books I wish I’d had as a kid.”

So, this week, to promote SWANA Reads and to celebrate Arab American Heritage Month, I thought I’d talk a little bit about my own childhood and the books I never had.

You don’t look like a Pilgrim

*Sophia from Golden Girls voice* Picture it, Rhode Island, 2004.

I’m sitting on the rug of my first grade classroom. I’m wearing my standard school uniform—green plaid jumper, white blouse, navy blue tights, black Mary Janes. My mom has wrestled my hair into a half-up pony tail, so it’s out of my face but my tangled curls still cascade around my shoulders. It’s my second year as a student at St. Brendon’s Catholic School, where I am one of two non-Catholic students in my grade.

“Mrs. [Teacher],” I ask. “Who are you voting for?”

I can remember the look of surprise on my teacher’s face when I asked this. I don’t think you typically get a lot of questions about your personal politics teaching first grade.

“Well first of all, you shouldn’t just ask people that,” she tells me. “Because they might think it’s rude. But I don’t mind telling you that I’m voting for George Bush.”

Next I ask my favorite question. “Why?”

She thinks for a moment, then replies, “because I’ve had a good last four years, and I don’t see a reason to change things. Now, back to story-time . . .”

This was an example of one of my infamous “off topic questions” I’d often get notes sent home about. It’s not that I was a bad student—but my curiosity (and lack of hesitation to vocalize said curiosity) had a tendency to derail the class.

There were fifteen of us total. If I really tried, I could still list all of their names, but I’ll give you the broad strokes—there were eight boys, seven girls. Of the boys, all were white except one. We’ll call him John. John’s family immigrated from the Philippines, so he spoke English with a bit of an accent.

In first grade, he was labeled as the “problem child” of our class. I remember he would be sent to the principal’s office more days than not, usually for speaking out of turn or taking his shirt off. I remember he had this bit, where he’d throw his shirt up and start stroking his abdomen, shouting, “I’m so sexy!”

The Catholic school teachers really didn’t like that.

Still, in his own strange way, John was brave. He didn’t let the constant trips to the principal’s office or red-faced lectures from our teacher get him down. I remember being a little jealous of that.

As for the girls, it was a sea of pale faces and big blue eyes. Except for me, of course, and the little Italian girl with bangs that all our teachers struggled to tell apart from me.

Halfway through our kindergarten year, we gained a new student, a girl who we’ll call Kate. Kate’s mom was our white Girl Scout troop leader, and her dad was Black. They were not the first biracial family I had ever met (obviously) but they were one of the only Black families in our majority Irish Catholic school. So, I can’t really blame our white peers for being a little confused when it came to my background by comparison.

“Is your dad Black?” they would ask me, because they could clearly see I was not one of them.

But, no. In fact, my dad is my white parent. He’s always had a darker complexion than my Arab mother thanks to his Sicilian ancestry and a life spent working outdoors. But try explaining that one to a bunch of six-year-olds.

The icing on the cake for this whole social experiment that was my early education was that my parents were freshly divorced when I entered kindergarten. I was not the only kid with divorced parents in our class—but I was the only brown kid with divorced parents.

I’m not going to sit here and boo-hoo about how hard that was, because, frankly, it could have been way worse. I will however share what is, in my opinion, the funniest microaggression of my time at St. Brendon’s.

I’m not sure if the school decided to be intentionally dated with their curriculum or if the textbooks we had were from the 1970s, but when we learned about the first Thanksgiving, we were told that it was a peaceful dinner between the Pilgrims and the “Indians”—the first Americans! We were armed with construction paper and glue sticks and told to make ourselves either a feathered headband or a hat with a big belt.

At recess, we conferenced in our misunderstanding. If the Pilgrims and the “Indians” had been the first Americans, we must all be descended from them, right? Well—except John, who was born in the Philippines.

A lot of my friends happened to know that their ancestors came over on the actual Mayflower. So of course, they would be playing Pilgrims in our kindergarten re-enactment.

“I’ll be a Pilgrim too,” I decided, wanting to fit in.

But one of the other girls shook her head. “I don’t know. You don’t really look like a Pilgrim.”

“Yeah,” the others agreed. “You’re probably an Indian.”

By the end of recess, I had decided to embrace this and proudly marched back into class to finish my wildly appropriative headwear. We loaded our table with plastic food and feasted on fake history.

When I got home, I asked my mom if it was true we were descended from “Indians."

My poor mother had never looked so confused in her life. She thought I meant Indian like, from India. “No honey, we’re Syrian. You know that.”

I did know that, because for my whole life up until that point, whenever I stomped my little feet and declared, “I’m seweious!” my mom would pretend not to understand and say, “I KNOW you’re Syweian.”

Mom jokes.

We went back and forth across the dinner table for awhile until she eventually realized I was talking about Native Americans, and burst out laughing. She then explained that no, not everyone in America today is descended from the guests of the first Thanksgiving. While my friends could trace their ancestry back to the Mayflower, our family had not in fact immigrated to the US until the twentieth century.

Looking back, the whole scene is pretty hilarious. I like that story because I think it’s a pretty clear-cut example of the way ignorance can rapidly transmogrify into racism, but I don’t hold any of that against my kindergarten classmates. How were they supposed to know any better? This was our world. Out of all fifteen of us, only three did not share in the monolithic European ancestry of “middle America.”

Not to mention I was not Catholic, born in sin, and a child of divorce. Weekly bible study was always a treat—although, first grade was also the year I found out I did not have to participate in Lent like the rest of them, and I will admit to feeling pretty smug about it.

Of course, by this age, my world was not completely isolated to the classroom. I watched the news with my mother every morning, and often again in the afternoon with my grandparents. I knew about the presidential election, and the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. I heard Toby Keith on the radio singing about how you’ll be sorry you messed with the U.S. of A. and grown-ups calling The Chicks unAmerican for their horrible attack1 against H.W. Bush. Whenever the news reported casualties in the wars oversees, they’d compare the number to the casualties of 9/11—never forget, right?

So, as a six-year-old who didn’t look like a Pilgrim, and who was constantly inundated with images of these veiled terrorists from the Middle East who wanted to subjugate me and my family and take away everything we held dear, and who heard grown-ups openly mock anyone who said differently—not just for their political views, mind you, but for their waistline—how was I supposed to feel anything close to pride about my heritage?

I wish I could go back in time and become better friends with Kate and John. I wish I had known the words to ask them about their experiences in our classroom and with our peers. Did they feel as isolated as I did? Were they afraid to talk about it, too?

But that’s the thing about words. We learn them from each other—from our classmates, from our parents, our teachers, our librarians and of course, our books.

The books that weren’t

When I was very young, there were no books about little Arab girls finding self-actualization. If Arabs did appear in media, they were probably the bad guys or, at best, misguided youth who would die tragically as a consequence. Arabs and Muslims were not human to Americans in the wake of 9/11. And so I grew up questioning my own humanity, my right to exist, my worth.

I didn’t have the words to talk about this with my family. We would get together and eat all our favorite foods and tell stories and laugh and be unapologetically ourselves—but that’s because we were “the good ones.” Our ancestors had been driven out of Syria by an anti-Christian Muslim regime. When we docked in Boston, we accepted a new anglicized name—Abraham, not even close to our original family name, but a translation of my great-great-grandfather’s first name, Ibrahaim. They renamed him John, and my own grandfather was named after him. We accepted cultural assimilation at the cost of thousands of years of our family history. But that’s the price of the American Dream, right?

In seventh grade geography, we were assigned a debate on Israel v Palestine2. Our teacher introduced the nations as, “Israel, ally of the United States” and “Palestine, a Muslim nation.”

I was assigned Palestine and I’ll admit, my gut reaction was, “aw man, I got the hard one.” Looking back though, my teacher definitely knew what she was doing.

The staged debate came to a head when me and some tiny white boy with a shaved head were the only two left standing. He was shouting about how the US should just put a dome up around our borders and never let any one else in. I pointed out that this made no sense, since a majority of Americans were descended from immigrants. His clapback was okay, fine, we just shouldn’t let people come here from the Middle East then.

“Then I wouldn’t be here,” I said. “My family is from the Middle East.”

His face changed. He shifted gears from arguing with me to full dismissal. “Oh, so you’re a terrorist?”

That was when our teacher finally intervened and declared the debate had ended. I was stunned. No one had ever called me a terrorist before—I was one of the good ones! At least, that’s what my family always taught me to believe.

It was in that moment I realized, there’s no such thing as “the good ones.” We’re either in it together, or we’re helping the destructive force of the colonizer win.

It wasn’t until I got to college that I really learned how to be proud of my heritage. I got out of my hometown, I met other people of color, I read books and attended lectures and followed activists I admired online. I have come to learn that cultural reclamation is an act of resistance. I refuse the melting pot. I refuse to stay silent.

I don’t want to sit here and whine about how hard the last few months have been for me, an American living thousands of miles away from the atrocities committed by the colonizer state of Israel against indigenous Palestinians on their own land, on their own holy days. I am so lucky that my family that remains in Lebanon is far away from any of the destruction. But I would be remiss if I didn’t mention how frighteningly reminiscent these last six months have felt. There have been moments that reduce me to stunned silence just like that day in 7th grade. Moments where I’m not an enlightened 26-year-old socialist anymore, but a scared little Arab kid during the Bush administration.

The world has changed a lot in the last 20 years. Instead of letting silence get the better of me, I speak out. I post about the genocide online. I call it what it is, and I demand others do the same. I see hoards of my pale faced blue-eyed American peers take to the streets dressed in red and green and black, outraged by the actions of our government. I am not alone anymore.

And of course, now, there are books about strong-willed Arab American girls who take pride in their heritage. I could recommend a few—but instead, I’ll just steer you towards SWANA Reads again.

Sorry if this got a little overly sentimental. I hope it was a good story, at least. And I hope you’re taking care of yourself, wherever you are. Let us all pray to whatever entity guides us for an immediate ceasefire, and for a Free Palestine 🍉

For the record, all Natalie Maines said was that she felt ashamed that the president claimed to be from Texas, where the Chicks formed. I wouldn’t personally categorize that as an “attack” against him, but hey, I’m just a dirty lib.

This would have been about 2011, for anyone who still thinks the war started on October 7th 2023.