Last week, I took you all down a mini-spiral with me about the very nature of binary systems and the hazy line between fact and fiction. If you missed it, you can check it out here—or, you can brazenly read on sans context. (Between you and me, I think you’ll be fine.)

My last post ended thinking about the how of storytelling—what are you trying to say, and who are you trying to say it to? When we analyze media (books, movies, etc), we often call this the lens.

In part 2 of this essay, I’m going to talk more about lens and how it relates to genre and the structure of the story. But before I do that, I have to bust down one more false-binary.

If you ask a hundred writers to define these terms, you’d get a hundred different answers—literary is lofty, commercial is basic; commercial is interesting, literary is boring; literary is intellectual, commercial is vapid; commercial sells, literary flops—so on and so forth.

In a Bookends article, writer James Parker offers the same axiom I became familiar with in my years of bookselling:

“We could say that commercial fiction is the stuff people want to read, while literary fiction is the stuff they think they should read.” (Parker, 2019)

I saw it time and time again—a big literary title would come out three, maybe four times a year. There’d be a big surge of sales the first couple weeks, but hardcovers are expensive. Even in the bougie town where I worked, most people were willing to wait for the paperback of whatever award-winning novel they heard about on NPR.

Contrasty, the sale of “commercial” titles—gorey murder mysteries, sexy romances, exhilarating adventure stories—flew off the shelf, and kept flying as hardcovers despite the hefty price. Jim Accountant and his housewife simply cannot wait the customary 12 months for the new Lee Child to be out in paperback.

Eventually, those literary titles would come out in paperback—and there’d be another surge in sales, this one bigger than the initial release. Literary titles have a decent chance of finding a permanent home in the Fiction section, if they live up to the hype. People will continue recommending them and/or listening to old episodes of NPR for years to come. But in the world of publishing, this quiet success gets you nowhere. A publisher won’t shell out marketing money for a book they believe to be dead on arrival—they’ll gladly reap the benefits of your extended backlist sales as you inch, cent by cent, towards earning out your initial advance.

Commercial authors on the other hand? You’ll get card-board displays at every Barnes & Noble in America. They’ll send you on a release-week tour through all the major cities to the sales they already know are coming. If you have enough Instagram followers, you might even get some fancy first-edition incentives (paid for by the publisher) to encourage those precious release-week sales. They’ll throw lots of money at you—right up until that first week ends, when an invisible panel of judges will determine whether or not your book has performed well based on their unwritten rules. May the penguin gods of a random house have mercy on your soul!

So . . . yeah. It’s kind of like if publishing were a horse race, but the publishers control what horses even get out the gate. And this is the industry I’m trying to “break into” for some reason.

The worst consequence of this marketing mayhem is the way it changes the way writers think about their writing. I know writers who have had manuscripts turned down for being “too literary” or “too commercial” before getting anywhere near a marketing department—who decides what is one or the other, if we can’t even agree on what these words mean?

I had a light-bulb moment about this at my most recent MFA residency. A friend of mine was having one of those Imposter Syndrome moments—these come for all artists, at all stages. They’re like the hiccups—because she felt that her writing was too commercial for our program. At first, I couldn’t understand why. How could something be “too commercial,” what does that even mean? That it’s too universally appealing?

But then I realized—this may be artsy fartsy school, but it’s still school, and academics will always be capital-A Academics. And our program, as much as I love it, is full of “literary” writers, and literary writers often sit on a very high horse. Instead of measuring success by numerical value, they throw around words like “timely” or “lyrical” to convey the intellectual value of a book. This is where that, want to read vs ought to read dichotomy comes back around to bite us.

I told my friend to forget about the labels—she pointed out that the labels are how she defines her stories, how they are packaged and pitched to readers. And being deemed “commercial” has really worked out for her! She wasn’t benefiting from an education centered on the idea that we shouldn’t worry about the commercial value of our work—because the commercial value of our work is what funds our work.

Tonight: Publishing vs Academia. Who will win?

Eventually, I decided the best advice I could offer was to replace the term “commercial” with “genre fiction.” Because half the time when someone says literary, what they really mean is a fiction story that’s about conveying a certain message or theme. Genre fiction stories do this too, of course, but they get to do it with dragons. But when these proud “literary” people hear commercial, they don’t think of stories that sell well—they think of stories they see as cheap and/or devoid of meaning.

This is because a lot of ”literary” writers view being deemed literary as an indicator of worth. They believe that writing a certain way translates to being somehow more morally or intellectually valuable. Like they’re struggling with low advances from publishers is some righteous cross to bear for telling “important” stories—you know, the ones with adjectives you have to Google mid-way through a sentence to even understand what’s going on. Books that will go on to win very impressive stickers on the covers for awards that will grow metaphysically dusty on a shelf beside all the money the author didn’t make.

I’m being facetious—or, as a commercial writer would say: I’m being sarcastic.*

What I’m trying to get at is, the currency of worth is exactly that—a currency. Just like the marketing dollars a publisher may or may not deem you worthy of. It’s bullshit all the way down, and it depresses the hell out of me to see other writers using words that Publishing invented to hurt our feelings against one another. There is no such thing as “too literary” or “too commercial”—this is a binary system without legs, because it can only be defined by its opposition.

The truth is, “literary” and “commercial” are nonsense words. They can be leveled against you to mean whatever the person rejecting you wants them to mean; they can also be used to console you when you don’t hit the bestseller lists (those are so commercial!) or you’re turned down for a prestigious award (those committees only care about literary titles!) or your book gets a bad review (this one can actually go either way). But at the end of the day they’re nothing more than the shoebox, and if you wear them outside in the snow, you’ll liable to lose a toe.

If you are looking at the story you want to tell and asking yourself if it’s literary or commercial or too much one or the other—you’re trying to make your story fit into the nonsense shoebox of those terms. And if someone tries to tell you your story belongs in one of the nonsense shoeboxes, they’re doing a disservice to you and your art.

But what does this have to do with telling stories? Well—the label you slap on the outside of the box should reflect what’s inside. This is true when we buy cereal and rat poison, but when it comes to books, the science is less exact. I’ve already explained why literary and commercial are messy labels—but that’s not to say all labels are bad. Some can be pretty useful—like genres.

Is your story a romance? A thriller? A folktale? Some of my favorite stories exist at an intersection of genres—a romantic thriller, for example, or a thrilling folktale. That’s the beauty of adjectives, folks. They compound beautifully.

But the label of the genre is a promise to your audience. There are story structures and tropes that we have come to expect. Maybe you want to subvert those expectations a little—that’s part of the fun! The problems arise when we try to police and gatekeep these labels as if they’re something a body of work needs to earn or live up to, rather than the lens through which we view it.

As the artist, it’s hard to control what lenses your audience is going to bring to your work. But as the writer, you have some control over how that lens gets shaped. Am I getting too metaphorical?

How we tell a story can come down to the language we use—some literary people feel pressured to use the biggest, fanciest words they can find to live up to the expectation that word literary suggests. *But remember that joke I made a few paragraphs ago? The punchline was that facetious is a “bigger” word than sarcasm. If you thought that was funny, thank you—but if it made you roll your eyes, you’re absolutely right. We have now reached the part of the newsletter where I will explain to you why my own joke was bad.

Don’t those two words evoke slightly different understandings? They aren’t perfect synonyms; the former means “to treat serious issues with deliberately inappropriate humor;" the latter, “the use of irony to mark or convey contempt.” Irony often takes the form of deliberately inappropriate humor and can also convey contempt. But facetious sounds somehow fancier and academic, while sarcasm makes us think of teenagers.

This is how I walk you to the conclusion that the SAT-merit of a word actually has very little to do with its storytelling quality, which deserves its own entire essay, but here I’ll cut to the chase—there is no value in pretty words if that is all they are. A story that hits all the right beats to be compelling but lacks artistry in the telling isn’t likely to make it on any Top 10 Books of XYZ lists, but if A Court of Thorns and Whatever has taught us anything, it’s that readers will always be reading.

And now, we have arrived at my third and final false binary (for now).

Raise your hand if you’ve ever felt frozen, staring at the blank page with an entire story ready to spill out of you but unable to actually write a single word because of the irritating voice at the back of your head that won’t stop asking—”what if it’s bad?”

What if I’m wrong? What if no one likes it? What if everything is garbage and hope is lost?

These questions are holding hands with literary or commercial? because they are inspired by the same misbelief in the currency of worth. I’m sure you’ve been told, don’t let the fear of bad writing stop you from writing at all. I hope someone’s told you that, anyway, and if not: there you go, I just did. But I know better than anyone how hard it can be to take that advice for ourselves. Because, frankly, we’ve all read bad books.

But what makes a book good or bad?

Here’s an example of how that conversation usually goes:

Person 1: “Twilight is a bad book because it is sloppily written, falls back on over-used tropes, and has weird religious overtones.”

Person 2: “Twilight is a good book because it resonated with an entire generation of teenage girls and empowered them to read more.”

I’m not going to stand here and defend Twilight, but I’m not going to rag on it either. Because both sides of that argument make valid points—whether or not I agree with those points doesn’t really matter. None of us can go back in time and un-publish a book; once it’s out there, we’re stuck with it. We can’t erase its contribution to the conversation anymore than we can make our annoying uncles shut-up at family dinner. It’s almost like nuance is important, or something.

A few weeks ago, I saw this post going around on Twitter:

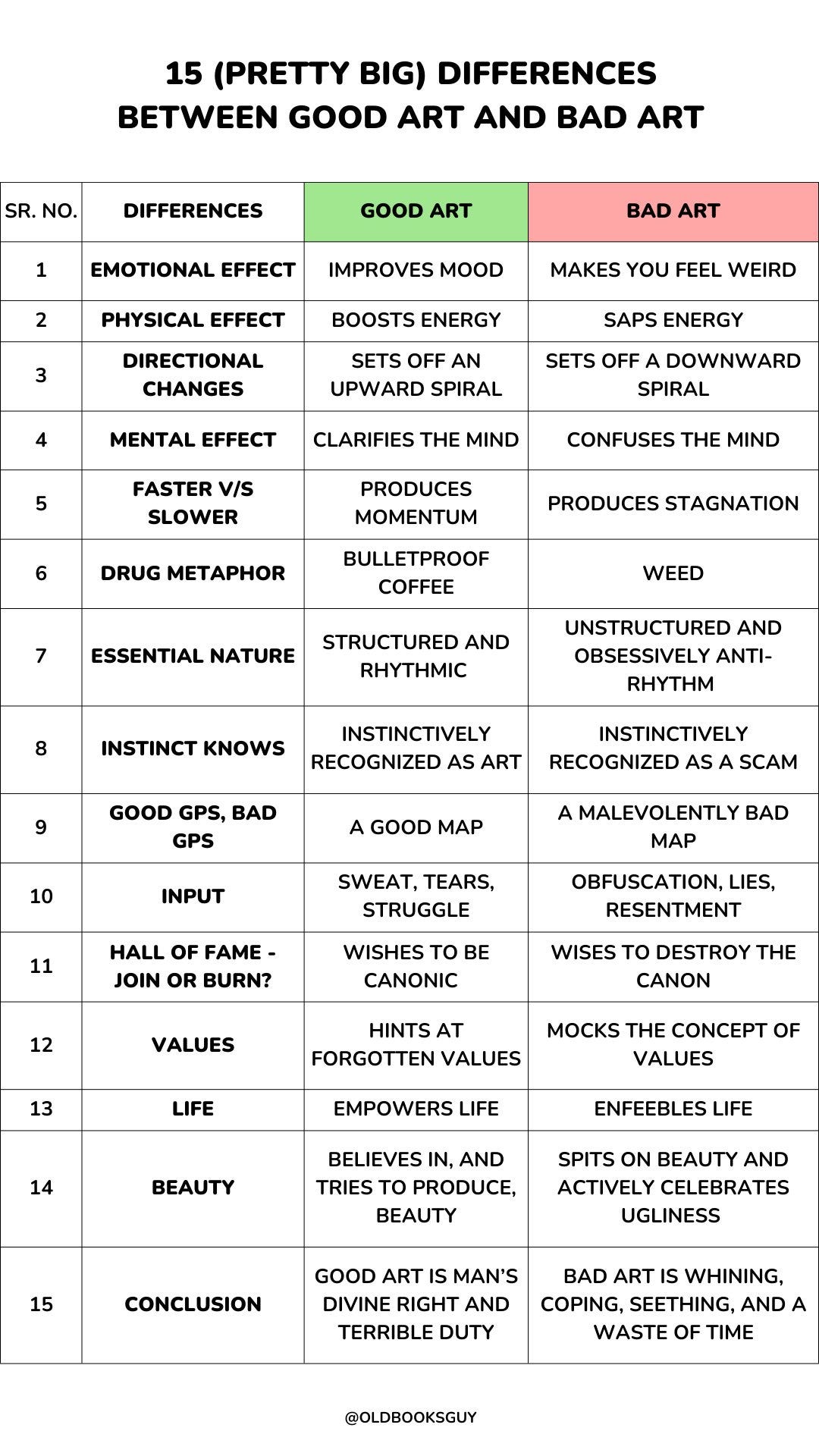

User OldBooksGuy posted this with the text, “The most annoying people in the world love to say there is no objective difference between good art and bad art. So I made a list of 15.”

Knock knock! It’s me, the most annoying person in the world.

For anyone with critical thinking skills, OldBooksGuy’s argument falls apart at the first point. If good art isn’t supposed to make us uncomfortable, I suppose any piece of visual or written art that tackles difficult subject matter is automatically bad. Elie Wiesel’s Night? Bad. 1984 by George Orwell? Bad. Toni Morrison’s Beloved? Bad. I could go on.

And hey, maybe you didn’t like any of those books I gave as examples—that’s your right. But the argument sounds pretty ignorant when you reframe it that way, doesn’t it? I mean, seriously, if we abided by, “it made me uncomfortable, so it’s bad” as a guiding principal in life, no one would eat vegetables or get vaccinated. It’s a blatantly immature take.

But that’s not to say art must make you uncomfortable, either. I’m a fan of art that makes me feel good—I hang it all over my walls! You can’t define the quality of something by the way it makes you feel because feelings are subjective. There is no objective good art or bad art—there’s just art, and how we feel about it.

Except for Robinson Crusoe, which isn’t even really art, if you think about it1.

As someone who will gladly argue the merit of reading Jane Austen or the Brontes as a modern reader, I take great issue with the belief that there is a “literary canon” of work. It’s elitist, and it leaves out anyone writing from the margins of society. It also allows some of the more problematic elements of so-called “classics” to persevere in the classroom—I’m talking about everything from the white savior-ism in titles like To Kill a Mockingbird and Huckleberry Finn to the casual racism, misogyny, homophobia, et cetera of older writers like Dickens and Shakespeare—and, yeah, even my girl Jane.

There is so much we can learn from reading widely—past and present. But we must read critically, with our eyes wide open. We must write that way, too.

We don’t get to decide how our stories will be received. Maybe you’ll set out to write the next great American novel and end up with the next Twilight—or maybe you’ll sit down to write your self-indulgent nonsense fantasy story and accidentally change the book industry as we know it. There’s no crystal ball for this, it’s just our best intentions.

The best craft advice I can give you is this: don’t put yourself in a box. Don’t limit your creative potential because you think your story should be a certain way. But do make intentional creative choices. Stay mindful of how you want the story to be told, and do your best to tell it authentically.

I tried to keep this part short since last week’s was such a bear—but thank you for sticking through it if you did. As always, I’m happy to see you here at the end with me.

Now go out there and make some kick-ass art. Much love,

Alex

This dig brought to you by Part 1 of this essay.